What happens when 5150 isn’t enough?

The Lost Legal Pathway to Court-Ordered Evaluation

A Level of Care Most People Cannot Reach

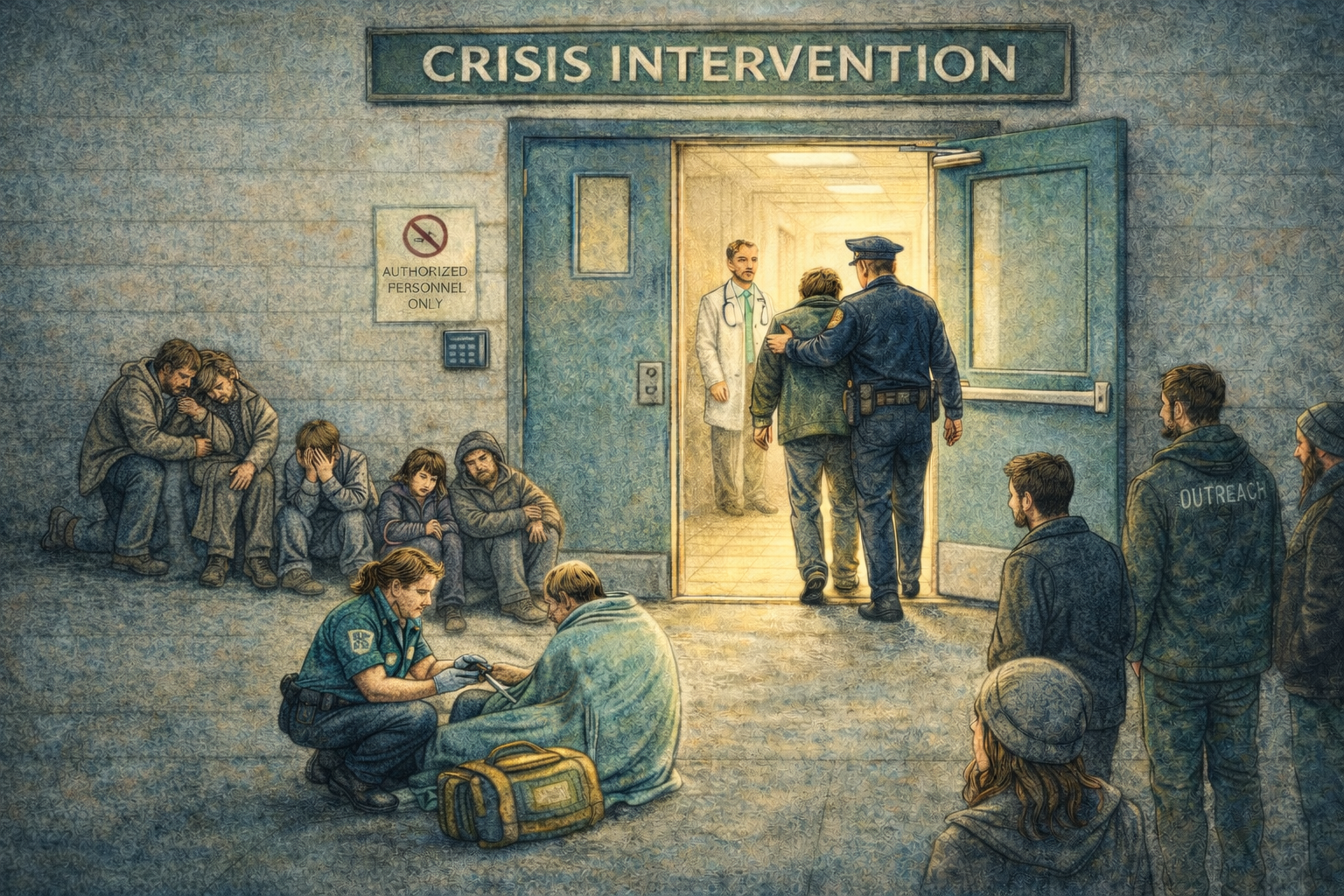

Across California, families, outreach teams, clinicians, first responders, and community members often try to get help for someone who is clearly deteriorating but unable to engage in care voluntarily. In these situations, the concern is not simply that a person is struggling. It is that, because of a mental disorder or severe drug use, they are no longer able to meet their basic needs for survival, to the point that they may meet the legal standard for grave disability.

At that point, they need care that can keep them alive, safe, and medically stable.

In most cases, the only way to reach that level of care is through a 5150 crisis hold. A 5150 hold protects a patient’s immediate safety. In some cases, it can open the door to a mental health evaluation or conservatorship. But it depends on what can be seen and documented in a single moment. Most of the time, a 5150 hold remains a brief, moment-in-time intervention and does not lead to the kind of evaluation needed to understand how serious the person’s condition really is over time. As a result, the person never gets to the level of care that could actually help.

For the people closest to the situation, this often means watching those they care for experience a steady loss of functioning. Housing is lost, medical and psychiatric conditions remain untreated, and the person is increasingly unable to obtain food, maintain personal safety, or navigate the services necessary for survival. Because 5150 holds focus on moment-in-time assessments rather than long-term evaluations, 5150 holds can often begin and end with no additional care. The need for a higher level of care is visible, but the pathway to reach it is not.

A Different Pathway Exists in the Law

California law already includes another option for situations like this.

It allows a court to order a full mental health evaluation when someone’s condition has become chronically serious. Unlike a crisis hold, this court-order process looks beyond the immediate crisis to develop a full picture of whether the person needs a higher level of care.

One important difference between this and the 5150 process is who can start the process. It’s not limited to peace officers and county-designated personnel. Under the law, a request can come from any person, including a family member, caregiver, outreach worker, first responder, or other member of the community.

It is not a new law. The court-ordered evaluation process is described in Welfare and Institutions Code Section 5200, and it has been part of the Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) Act since 1967.

In theory, this 5200 court-order pathway creates a way to reach people who are clearly in trouble, but who never quite meet the strict, moment-in-time criteria for a crisis hold. It offers the chance for a full, court-overseen evaluation that can include the people who understand the situation most closely. In practice, however, there is no clear or accessible way for this process to begin.

Assessment Versus Evaluation: A Difference That Matters

A mental health assessment and a mental health evaluation are often talked about as if they are the same thing. They are not.

A 5150 requires a rapid assessment. It is designed to answer a single question in a single moment: Is the person safe right now?

That decision is made by peace officers or county-designated personnel in a fast-moving environment, often with limited information and very little time to understand the full history of what has been happening. The hold can also be ended early if the person is seen to no longer meet the criteria by the reviewing emergency department. This subjective decision-making reinforces a 5150 hold as a moment-in-time safety decision. The hospital-designated assessor may or may not be a behavioral health professional.

A court-ordered evaluation is different. It is not a rapid screening. It is a structured process that must be done by a qualified behavioral health professional. It is designed to look more deeply at the situation.

Assessments and evaluations do different jobs. A crisis hold assessment is the right tool for an immediate safety decision. A comprehensive evaluation is the tool for determining the level of care a person may need if they are in a chronic state of crisis.

When only the first tool is consistently available, the outcome is predictable. Decisions are made based on a single moment in time. People may stabilize briefly and then return to the same crisis again and again, not because the need is unclear, but because the process being used is not designed to answer the larger question.

For many families, outreach teams, and first responders, this cycle is already well known. They are often watching a person deteriorate over months or years. They know something more is needed, even when the person does not meet the strict criteria for a hold in that particular moment.

When a system has only one doorway, it only sees the people who can fit through it. That does not mean others in need are not still out there. Their need is often obvious outside the door, but inside, where access to care is determined, the system only sees a narrowed view created by that single entry point, leaving part of the vulnerable population invisible or misunderstood.

This is why the distinction between assessment and evaluation matters. It is the difference between a system that can respond to an emergency and a system that can recognize the level of care that could change the course of what is happening.

Why This Matters in Practice

When there is no clear path to the level of care a person needs, the responsibility for managing the situation does not disappear. It shifts. Emergency departments, first responders, outreach teams, jails, courts, and families become the places where the consequences are addressed.

Each system of care is designed for a specific purpose. Public safety response addresses immediate threats to life and safety. Emergency medicine stabilizes acute conditions. The criminal legal system manages legal accountability. Families and community providers provide support. None of these systems was built to function as the primary pathway to long-term mental health care, but without access to entry points, they sometimes offer the only available aid.

The effects of this problematic system shifting are felt everywhere. The same vulnerable person shows up again and again, only to continue cycling through the streets, jails, and hospitals. The process relying solely on 5150 holds means that the person has to fit the limited system rather than the system responding to the reality in front of it.

That raises a practical question. If the current entry point cannot reliably reach the right level of evaluation, can Section 5200 provide this?

How This Was Examined

To understand how this pathway functions in real life, Public Records Act requests were submitted to all 58 California counties. The requests asked for any written policies, procedures, or publicly available processes describing how a petition under Welfare and Institutions Code Section 5200 could be initiated and carried forward.

This was not an effort to evaluate or compare individual counties. It was a way to answer a structural question: whether there is a clear and accessible method, anywhere in the state, for using a part of the law that has existed for decades.

Of the 58 counties, 46 responded. All responding counties reported that they do not have current policies or procedures describing how a 5200 petition would be initiated or carried forward. Some of the reporting counties directed the request to other existing processes, like 5150 holds, instead of identifying a pathway specific to Section 5200.

In a small number of places, there were still traces of earlier court-ordered evaluation systems. These included older court forms created for this purpose, references in training materials, or procedures that had once possibly made the process work. But those mechanisms do not appear to exist today as a clear, publicly accessible path.

In practice, this means the process described in the statute is not functioning as a distinct way to reach care.

At the same time, state-level materials from the recently enacted CARE Act reference Section 5200 as a part of the continuum of care. This points to a gap between how the process is positioned in statewide design and how it can actually be reached on the ground.

What This Makes Visible

In many communities, the barrier to care is often described as a lack of engagement by the patient or a lack of resources. By the time families, outreach teams, clinicians, and first responders reach this point, that experience is very real. The resources expended are heavy, but the available options rarely lead to a lasting change.

This may be a reflection of how the current entry criteria shape what becomes visible for planning. Systems can only plan for what they can see. Right now, what they see most clearly are short, high-intensity crises. Those moments draw attention and resources. But chronic vulnerability does not all look the same. Some people are living in situations that are just as serious, but in a quieter, ongoing way. When the only reliable entry point to a higher level of care is a brief, moment-in-time crisis standard, the people who do not meet that standard are difficult to count and difficult to plan for, even when their need is obvious to those closest to them.

Section 5200 offers a way to establish and document need beyond a single crisis encounter. It remains in the statute, and the State continues to point to it as part of the care continuum.

That means the core pieces are already here. The need is visible. The legal authority exists. What is missing is a practical way, at the county level, to connect them.

In that sense, the shift is not a large one, relatively speaking. It’s a small turn to bring what the law contains, what the system can do, and what people are asking for back into alignment.

This article is based on the larger white paper, “The Lost Legal Pathway to Mental Health Care,” by Quarter Turn Strategies.